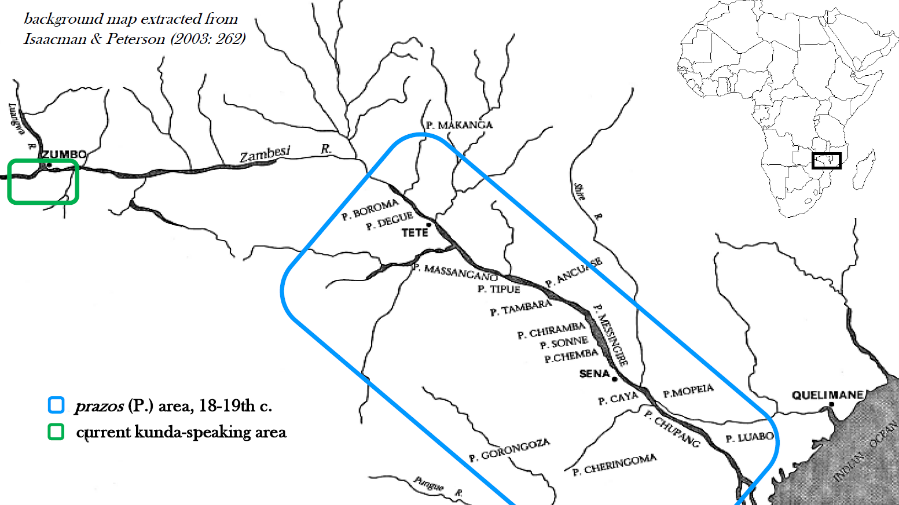

The OriKunda project (PI Rozenn Guérois) aims at revising the history of the Chikunda people and language from the origins to the present day, through historical linguistics, anthropological linguistics, and sociolinguistics. Originally, the Chikunda formed the soldier-slave troops working for the prazeiros, i.e., the owners of the prazos (territories in principle given in concession to a white captain for a period - prazo, in Portuguese - of three generations) along the Lower Zambezi River in central Mozambique (blue area on the map below). These slave soldiers had the task of collecting local taxes, maintaining order in the prazos and protecting them from possible external threats. They also participated in the production of wealth through hunting and trade. These soldier-slaves generally came from distant geographical areas, north of the Zambezi River. A descendant of a family of prazeiros indicates: “In the beginning the Kunda were not a tribe. They were a mixture of people who came from far away.”[1] Linked by their destiny as warriors and hunters, these slaves gradually forged a new identity, based on the values of courage and military discipline, an identity marked by practices and beliefs that distinguished them from the indigenous peasant populations; they became the Chikunda, that is the “conquerors”. The term kunda comes from the Shona verb kukunda which means ‘overcome’ (Isaacman & Peterson 2003: 268). The first explicit reference to the Kunda dates back to the 18th century (Newitt 1973). Their number is estimated at 50,000 in the middle of the 18th century (Isaacman & Peterson 2003: 260).

From this new identity was born Chikunda, “a language without a land […] a mixture of Atawara, Azimba, Makanga, Quelimane, Atonga, and Barue”[2], that is to say different Bantu languages spoken in central Mozambique, but supposedly with a predominant Sena base, another Bantu language, spoken in the prazos area. With the collapse of the prazo system in the 19th century and the emancipation of slaves, the Kunda had to rethink their identity. Some returned to their native land, others stayed and blended into the local Sena populations located on the southern margin of the Lower Zambezi. In both cases, they waived their Chikunda identity. However, a group of former Chikunda slaves preserved their identity and took advantage of the political instability of the time to engage in territorial conquest. They were nevertheless defeated by the Portuguese colonial army in 1903. Following this defeat, the Chikunda retreated west in a remote region at the confluence between the Zambezi and Luangwa rivers, which today corresponds to the border area between Zambia, Mozambique and Zimbabwe (in green on the map).

The unique history of the Chikunda people and their language raises three major fascinating questions, which come under three sub-disciplines of linguistics, and whose approaches are complementary.

- Historical linguistic component: What is the genesis of the Chikunda language?

- Anthropo-linguistic component: What does Chikunda cultural vocabulary tell us about Chikunda history? To which extent is Chikunda history reflected in its cultural vocabulary?

- Variationist and interactional sociolinguistics: How do Chikunda speakers effectively speak? How is the language used in space and time? Are there several Chikunda varieties or dialects? If so, how do they differ from each other? Which attitude and discourse do the Chikunda speakers entertain vis-à-vis their language? Which representations does Chikunda convey?

References

Isaacman A & Peterson D (2003) Making the Chikunda: military slavery and ethnicity in Southern Africa, 1750-1900. The International Journal of African Historical Studies 36(2). 257-281

Newitt M (1973) Portuguese Settlement on the Zambezi. New York.

[1] Extracted from Isaacman & Peterson (2003: 261), originally from an interview with Ricardo Ferrão (October 1997).

[2] Isaacman & Peterson (2003: 269), from an interview with Conrado Msussa Boroma (July 1968).